Smaller Can Be Beautiful

When the Dead resumed touring in 1976, after a 21-month hiatus, PA technology had advanced sufficiently that it was no longer necessary to isolate each instrument and run it through a separate speaker system—not to mention the fact that it was economically impossible to truck those mountains of gear around.

“Efficiency comes down to the number of boxes that you have to carry, of weight in a semi-truck going down the highway,” Healy observes.

Not only was it impractical, but it was no longer necessary. In the intervening years, what Healy and the Dead wanted—a system that performed as well as the Wall of Sound, but which was “one fourth the size and four times as efficient”—came into existence. “The system we have now is better than the ‘74 system, overall, even though the ‘74 system may have been better in certain ways.”

The Dead currently tour with a PA owned by Ultra Sound, using speaker systems and associated electronics by Meyer Sound Labs. “Meyer has been able to extend the low and high frequencies without hopelessly distorting the rest of the sound,” Healy notes. “That’s actually the main significance.” And by arranging the speaker cabinets to work together in a very precise way across the whole frequency spectrum, it takes fewer drivers to cover the desired area, and intelligibility is uniformly good nearly everywhere.

With the quality of the PA hardware firmly in hand, Healy says that the Dead’s concert setup these days goes through subtler changes and refinements.

One interesting development came to Healy almost by accident, and resulted in a very useful device to make his job easier.

“The vocal mike is the loudest one in the mix,” he explains, “and if it’s open on the stage it’s picking up drums or guitars from 15 feet away, and adding them in 15 milliseconds later—which is that many degrees of phase cancellation—and the net result is a washing-out of the mix. You can’t use audio amplitude to gate those mikes, because the guitars are frequently louder at the mike than the voice that’s standing right in front of it.

“So a certain amount of me always had to be on the watch for the singers so I could turn their mikes on,” he continues. “That was annoying, and it kept me from being able to listen on a more general level.

“The Paramount Theater in Portland, Oregon, has a balcony that’s right on top of the stage. I was looking down at the guitar players, and it all connected for me. I’m a musician myself, and I know that one of the most embarrassing things that happens when you’re playing rock ‘n’ roll is running into the mike and banging yourself on the lip or being a mile away from it when it’s time to sing.

“That night in Portland I realized that every musician has a kind of home base where he puts his foot in relation to the stand so he knows he’ll be right at the mike. It was duck soup: I got the kind of mats they use to open doors at the grocery store, then designed and built the electronics that gated the VCAs [to control the mike-preamp gain], and lo and behold, it worked!”

For keyboardist Brent Mydland, the situation wasn’t so simple. John Cutler, who works with the Dead in R&D as well as other capacities, designed a system around the sonar rangefinders used in Polaroid cameras. Using discrete logic rather than a full-blown microprocessor, Cutler came up with an automatic gate that opened the mike when Mydland’s head came within singing distance of either of his two mikes.

“It’s just one of those things that came about as a means to an end,” says Healy. “I built the floormat [device] just so I could be freed from switching on microphones.”

Rather than get involved in marketing a device like this, which Healy says is “not my business,” he just has a few extra circuit boards made. “If somebody comes by and wants to try it, we give them the cards and a parts list.”

Because every Grateful Dead gig is different—no songlist, plenty of room for instrumental improvisation, no pre-arranged sound cues to speak of—mixing for the band has never settled into a routine for Healy.

“Some nights they start out screaming and get softer, and some nights they start in one place and stay there,” he says. “There isn’t really any good or bad in it—it’s just a different night in a different way. From the start to the end of the show, it’s a continuous progression, figuring out how to spend the watts of audio power that you have in such a way that it’s pleasant and human.”

It’s been years since Healy went into a hall and pink-noised the sound system. “I leave my filter set flat, and I dial it in during the first couple of songs. After enough years of correlating what I see and hear, I know what frequencies, how much, and what to do with it.”

Test equipment is on hand for reference, but Healy prefers to rely on his ears. “You have a speedometer in your car, but you don’t have to use it – or even necessarily have it. You don’t need it to know how fast you’re going, but it’s there for reference: That’s how I use the SPL meter and the real-time analyzer.”

In the “hockey-hall-type spaces” the Dead play in these days, Healy likes to set up about 85 feet from the stage.

“In my opinion—and my opinion only, for that matter—the ideal combination of near-field and far-field is 85 feet. I don’t like to be far enough into the far field that it’s a distraction, but for me it’s important to hear what the audience hears. Healy considers himself the audience’s representative to the band, comparing notes with the musicians after shows, and telling them things they might not want to hear “if I feel I have to.”

He also encourages—within reason—those members of the Dead’s following who bring their recording gear to concerts.

“I’m sympathetic with the tapesters, because that’s what I used to be,” he says. “I remember buying my first stereo tape machine and my first two condenser microphones, sweating to make the payments, and going around to clubs and recording jazz. So I’ve sided with the tapesters, helped them and given them advice and turned them on to equipment.

“I learn a lot from hearing those tapes,” he continues. “The axiom that ‘microphones don’t lie’ is a true one. If you put a microphone up in the audience and pull a tape and it doesn’t sound good, you can’t say, ‘It was the microphone,’ or ‘It was the audience.’ You’ve got to accept the fact that it didn’t sound good. When you stick a mike up in the audience and the tape sounds cool, it’s probably because the sound was cool. So it’s significant to pay attention to the tapes.”

Even after 18 years of working with the Dead, Healy says he still enjoys going to work every day. “I’ve been doing it so long that I don’t even look at it as a job,” he explains. “It doesn’t get stale for me on any continuous basis. I react more to ‘Tonight was a good night,’ or ‘It wasn’t so good.’ I can have a bad night and go home discouraged and kicking the dog, grumble-grumbie, but I’m always ready to start again tomorrow.”

Additional Coverage

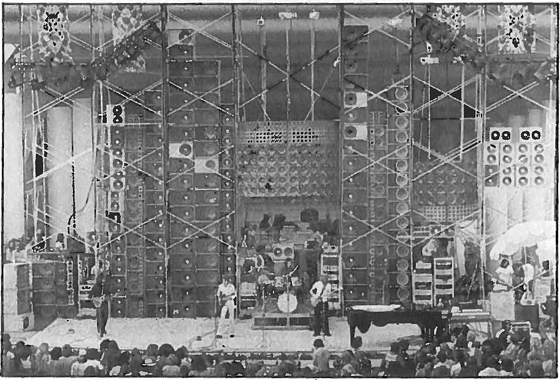

The Grateful Dead System At The Oakland Auditorium, December 1982

According to Howard Danchik of Ultra Sound, ‘‘The Dead’s system, as always, was run in stereo. The main speakers were flown, and comprised 12 MSL3s at each side of stage, plus a center cluster of eight (four lelt and four right channel), also above band.

“Suspended from the side clusters are three Meyer Sound Labs UPA cabinets, angled downward to fill in for those at the front of the audience. There are also four UPAs below the lip of the stage at the center (two left and two right) for the spectators at the very front-center, plus one UPA at the rear of each main cluster, pointed up and back for spectators in the balcony directly to the sides of the stage.

“Each MSL3 is driven by 650 watts RMS of amplification—225 to each 12-inch speaker (two per cabinet), and 200 to the four piezo tweeters. One MSL processor is used to drive all the MSL3s on each side; two (one per channel) to drive the center cluster; and two (one per channel) for the front and sidefill UP1As.

“Additional speaker systems included: for the lobby four UPAs (stereo, via Meyer processors); for the bars one UPA in each bar (mono, one processor each); the kitchen one UPA (mono, one processor); and the kids’ room a pair of Hard Truckers five inch cubes (mono, no processor).

“All power was provided by Crest amps, 225 W RMS per channel into 8 ohms. House mixer was a Jim Gamble custom board, 40-in/8 stereo submasters, wtth automatic built-in mono output The monitor mixer was a Gamble custom 40/16 console. House effects included a Lexicon 22/lX digital reverb and Super Prime Time; dbx Boom Box subharmonic synthesizer; a collection of vocal gates; and an autopanner, homemade by Dan Healy & company. Microphones included Shure SM78s for vocals, plus a new Neumann mike for Jerry Garcia, and Sennheiser 42ls, AKG C451s and C414s.’’

Editor’s Note: This is a series of articles from Recording Engineer/Producer (RE/P) magazine, which began publishing in 1970 under the direction of Publisher/Editor Martin Gallay. After a great run, RE/P ceased publishing in the early 1990s, yet its content is still much revered in the professional audio community. RE/P also published the first issues of Live Sound International magazine as a quarterly supplement, beginning in the late 1980s, and LSI has grown to a monthly publication that continues to thrive to this day.

Our sincere thanks to Mark Gander of JBL Professional for his considerable support on this archive project.