The year was 1927, and the global professional audio industry didn’t exist. But things were about to change.

It was the year that Al Kahn and Lou Burroughs established a fledgling enterprise they called Radio Engineers in the basement of the Century Tire and Rubber Company in South Bend, Indiana. At first, they focused on servicing radios and shortly after, the retailing of radio equipment. The invested capital was $30 and a second-hand car.

Fate soon intervened, however, and at first glance, cruelly. The Great Depression, which began in 1929, all but wiped out the aspiring business. “We found ourselves insolvent to the extent of $5,000,” Kahn noted in a company history written in the early 1950s. “To survive and pay our creditors, we began work in the audio field and liquidated the remnants of the service and retail business.”

The change of direction set the young entrepreneurs on a path of technological innovation in establishing a firm that became and remains one of the bedrocks of what we now most commonly call pro audio. The first significant milestone came during the early months of 1930, when Knute Rockne, the legendary football coach at the nearby University of Notre Dame, wanted to supervise activities on all four of the team’s practice fields from a centrally located tower.

(Click here to check out the EV timeline for a lot more history — including rare photos — of the company’s developments and milestones spanning 90 years.)

Kahn and Burroughs were asked to design a public address system for the tower, and they formulated a four-loudspeaker system with a microphone and switching mechanism by which Rockne could bark training orders to each of the four squads. Rockne referred to the system as his “electric voice” and is credited with inspiring the name for the new company.

Incorporated on July 1, 1930, Electro-Voice was involved heavily in the rental and installation of public address systems for churches and other public spaces. Politicians especially had become aware of the power of the microphone to increase their reach and demanded ever more powerful PA systems. Microphones were originally manufactured only for EV’s own use, but within a few years the balance had shifted and manufacturing mics for sale to others had become the more important part of the business.

Nearly nine decades later, microphones remain a staple, joined by class-leading loudspeakers and electronics, all of them further bolstered by the support of parent company Bosch GmbH, which acquired EV in 2006. It’s a serendipitous association, where as a member of the Bosch Security Systems division, EV benefits from Bosch’s own tradition and support of engineering-based solutions and leadership in a diverse range of global markets.

The result is a portfolio of options across every pro audio market while also encompassing a bigger picture by teaming with other divisions in the group, including Dynacord (electronics), RTS (intercoms), Telex (radio communications and wireless systems), and Bosch (video and security).

The vision that’s become a reality is an organization providing specialized technologies that work together seamlessly, most recently emphasized by OMNEO, an evolutionary platform for connecting devices over IP to exchange information, including control and audio content, facilitating, for example, commercial ceiling loudspeakers, security cameras, access panels, and ROIP/VOIP dispatch communications all working together seamlessly.

Problems & Solutions

The scope and scale of the EV portfolio today encompasses everything from commercial to concert sound, with products available for any application and budget. The overriding focus from the very beginning has been sonic quality, accompanied by other developments, many of them patented, that solve additional challenges.

For example, in 1934, while going through some old technical journals, Kahn came across what he called “an ancient watt meter – patented in 1892 or thereabouts” which had a balanced winding to cancel hum from the stray 60 Hz fields that the watt meter might pick up. As he described it, “A little light bulb went off above my head, and I rushed back… got some tin snips, cut some laminations out, and I made a transformer and put it in and it worked!”

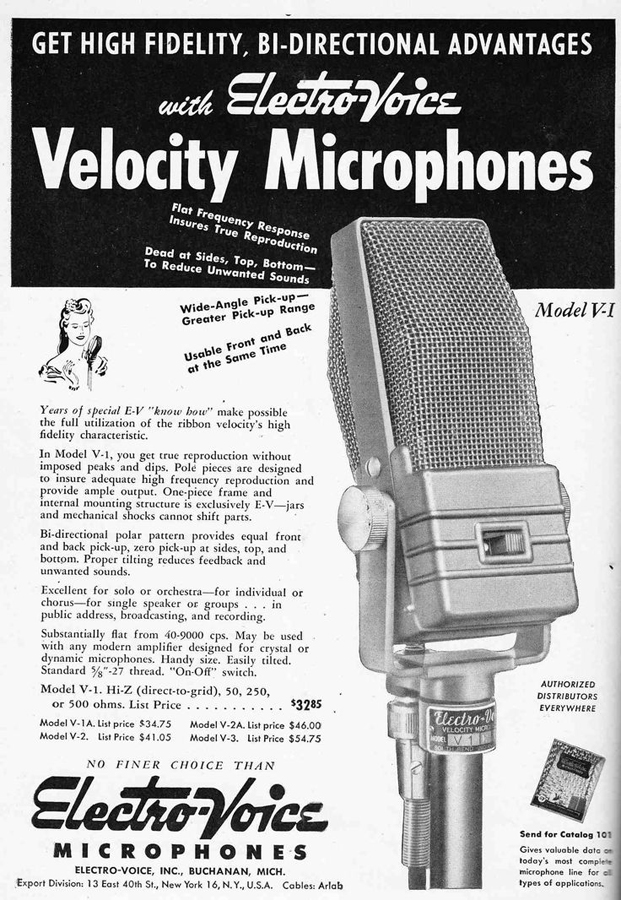

Thus the humbucking coil was born, eliminating a major problem for microphone users. The breakthrough was applied in the V-1 Velocity microphone, and according to an early EV catalog, it could “be used within 18 inches of a power supply or within two inches of an AC line. No other velocity mic in its price field has this feature at the present time.”

Kahn and Burroughs followed up the next year by developing a method for stretching dynamic mic diaphragms before assembly. The manufacturing economies that resulted caused a dramatic drop in mic prices, providing another advantage for users.

Within a few years, the company had created several handheld dynamic mic designs. An example is the Model 600, described in EV product literature as offering “blast-proof high fidelity, close talking… ideal for sports announcing, mobile PA, aircraft, police and general PA and communication work.”

Business grew steadily while Kahn and Burroughs spent much of their time traveling – “converting people to our marvelous microphones throughout the country,” according to Kahn.

This growing success continued through the years of World War II, including the development of a mic using a 180-degree phase shift to cancel background noise and engineered to be attached to the helmet and rest on the lips.

Dubbed the T-45, it raised the success rate of battlefield communications from 20 percent to at least 90 percent, saving countless lives in the process.

After the war, the rapidly growing operation transferred to Buchanan, MI, where it remained for almost 60 years over the course of several expansions.

The facility included one of the first anechoic chambers outside of a research laboratory, and eventually, the company also occupied a dedicated 28,000-square-foot research and development building in downtown Buchanan.

Another interesting note is the role EV microphones played in the rapid advancement of space flight from the late 1950s into the 1970s, beginning with early Mercury and Gemini missions through the Skylab space station. In fact, both mics and loudspeakers served Skylab during its six-year orbit, performing without failure despite a lost heat shield.

New Directions

EV also ventured into the consumer side of audio in the 1950s, beginning with a line of phonograph (record player) cartridges followed by hi-fi loudspeakers, becoming one of the largest suppliers in the U.S. But the primary focus remained on the pro market, exemplified by the introduction of Variable-D microphone technology, which reduces proximity effect. It’s at the heart of many RE Series microphones still in circulation to this day, most prominently in broadcast applications, highlighted by the venerable RE20 and most recently, the RE320.

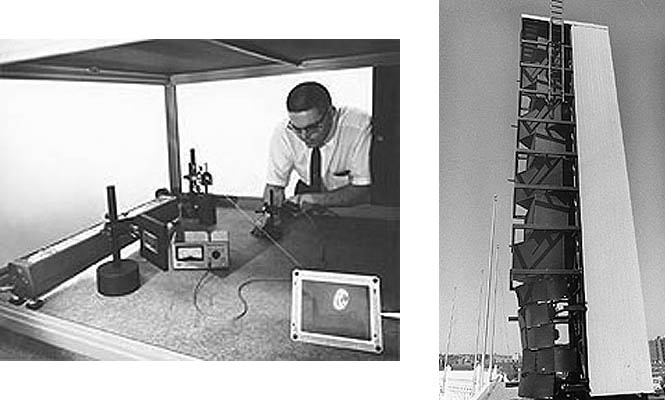

With a patent count that topped 160 by 1980, the company continued to push in a number of beneficial directions. In the early 1970s, EV pioneered the use of holographic interferometry (laser technology) to study the motion of mic diaphragms. Initial efforts were done in partnership with the University of Michigan, and later the process was brought completely in-house.

While EV was also known for its commercial loudspeakers, by the early 1970s serious attention was paid to furthering true professional loudspeaker technology.

The company embarked on an aggressive program of compression and driver development, both for its own loudspeaker systems as well as for third-party systems.

Simultaneously, this period saw the development of constant directivity (CD) horn technology, which dramatically improved high-frequency performance and control. The innovative horns were also light in weight, which came in handy when they were specified by noted consultant Bob Coffeen as the key components in the sound reinforcement system serving the new Silverdome in Pontiac, MI, a huge indoor sports stadium with an air-supported roof, so the light weight of the horns was a necessity.

Around the same time in the mid-1970s, Dave Klepper and Larry King of Klepper Marshall King specified CD horns for the 1976 Yankee Stadium renovation project. “We sold them our ‘line array’ – heard that term before? – made up of a huge stack of HR horns mounted in a steel structure above the outfield,” recalled Jim Long, who worked with EV for more than 40 years and remains affiliated to this day. “There was also a whole bunch of our CDP commercial horns to cover shadowed regions of the main grandstand.”

“The dealer couldn’t equalize the system, didn’t know enough about tuning, didn’t have a spectrum analyzer, had never seen a third-octave graphic EQ, which were still kind of new then,” he continued. “So I, along with some EV technical folks, came out and worked with Larry King on tuning. I don’t even know for sure that we knew exactly what we were doing, but that system was there for a long, long time.”