“The most important piece of equipment in a recording studio is the control room,” says Phil Greene, chief engineer and part-owner of Normandy Sound, located in Warren, Rhode Island.

It’s that kind of thinking that led Normandy, one of the first 24-track studios in the region, to become the first facility in the six states to feature a certified Live-End/Dead-End control room.

Since the new room opened last October, business has been good, but that’s not necessarily due to the new control room.

One of the more important clients has been Billy Cobham, who came to this mill town from his home in Switzerland, on a blind recommendation from his bassist Tim Landers, to record two albums that were quickly picked up by Elektra/Musician.

R-e/p spoke with Normandy’s chief engineer Phil Greene on two occasions: the first was in January, while tracks for the Cobham session were being laid; and the second was in March, right after Cobham’s tour with Bobby and the Midnites, during the grueling 12-day mixing session.

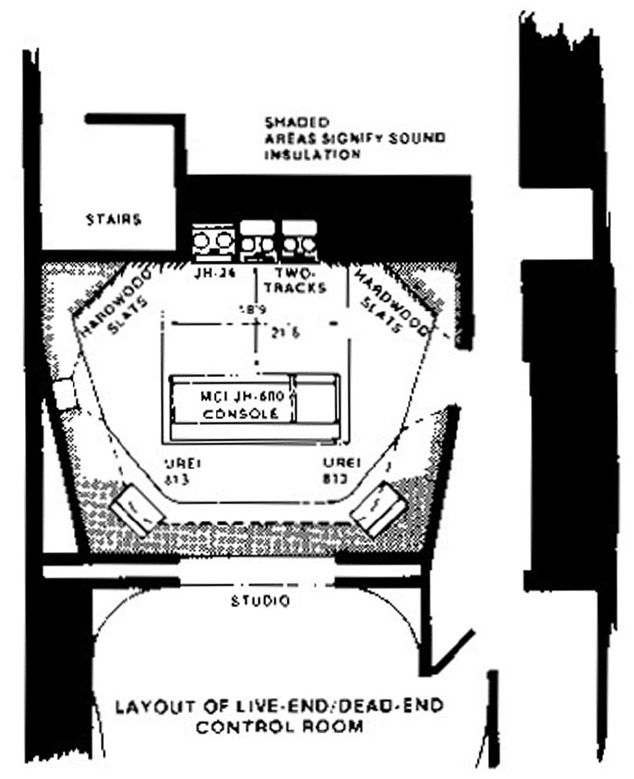

Greene wastes no time explaining what the LEDE concept means to him. “It’s as close as you can get in reality to an anechoic chamber at the front of the room,” he says.

“Obviously you have the window and the console, but there is an essentially uncolored signal path between the speakers and the ears, with no phase or frequency-response abnormalities — you hear the speakers, not the walls.

“Of course, if the whole room were an anechoic chamber, you’d go crazy, so the rear wall is diffuse reflective, more or less centered towards the mixing position.”

“Not only does it recreate some ambience, so that you don’t put huge amounts of reverb on the tape, it also improves the sense of where sounds are coming from in the stereo field.”

Arguments can be (and are) made that such a “clinical” environment bears no relation to the outside world, and that this concept is just another room that a producer has to get used to before his or her product will translate well to the street.

But Greene still feels it is useful. “Of course it’s unrealistic; every listening environment is. But what this concept does is eliminate one generation of listening error, which is the almost random effect that a room usually has.’‘

The Conversion Process

Normandy’s old room was well respected for its accuracy, and it wasn’t an easy decision to rip it out and start over again.

“I wasn’t unhappy with the old room, to be totally honest,” Greene admits.

“It was ‘splashy,’ so I tended to mix things dry. Sterling Sound, who does most of our disk mastering, commented at one point that our product was a little dry. The room also had a hyper-preciseness that was unnatural.”

“It would tend to dry up the bottom, so that those tracks were always too separate — it was hard to get them to blend. We thought we should be able to do a better job monitoring.”

“If you’re secure in knowing that what you’re hearing is what’s really there, then you can make a good record, no matter what your equipment is like.”

“We’ve stressed that attitude ever since we first opened as an 8-track. We were comfortable with the old room, so going with LEDE wasn’t a necessity for us, but it was a good choice.”

“When I was looking around for a design, everybody sent me to Don Davis. I had agreed with the theory for years — it’s pretty hard to shoot holes in — but it seemed that it might be so far ahead of the real world that it might turn out to be too exotic.”

“We talked to the folks who designed the [New York] Record Plant, which is a great room, but they seemed to play a lot of it by ear, and I wanted a design I knew would work right the first time. It was a little discouraging when I went to a few rooms in the area that were uncertified attempts at LEDE, and they were total failures.

“What finally clinched it for me, however, was an interim step we took when we removed the ceiling from the old room, and just left the insulation and the cloth covering hanging there — sort of a Dead Top. I loved the mixes I found myself doing, and I realized this was the way to go.”

Considering the amount of work that had to go into the new control room, it was done very fast — downtime was about a month. Dan Zellman of Howard Schwartz Studios, New York, an engineer certified in LEDE design and measurement, came up to the studio and did the blueprints in a few days.

Then, the existing room was torn down to the outside walls, an asymmetrical outer shell was put in, and the symmetrical room was built inside of that. The carpentry was handled by two local builders, Alan Souza and Gary Fenster.

“Alan’s an artistic type,” offers Greene. “Most carpenters in a studio situation get blown out by the number of intersecting odd angles they have to deal with.”

“This guy loved what he was doing, especially when things weren’t rectangular. The blueprints were very precise, so there wasn’t much margin for error.”

“We started out with soft fiberglass on the front walls, but it was a little too anechoic for our taste— it soaked up too much sound, and the whole room was a few dB short on level. We replaced it with harder stuff: a thin version of the material they use to insulate boilers.”

The frame itself was heavily overbuilt, with double studding and two layers of sheet rock. “It’s got to be solid,” Greene says. “If the walls move, it defeats the whole purpose.”

Meanwhile, Bob Windsor, one of Normandy’s engineers, was working on the new wiring harness (along with the control room, Normandy was putting in a new MCI JH-600 console and JH-24 multitrack).

It took about 36 hours to install completely the harness and recording equipment after the room was finished. The final step was certification.